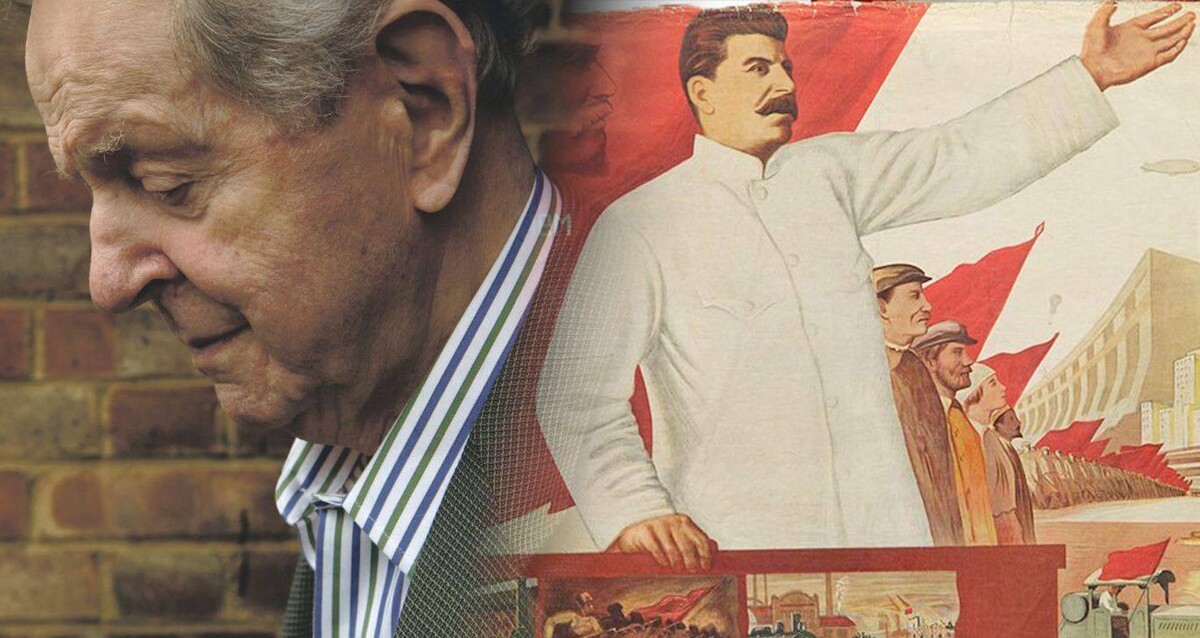

This is the story of a civilization that, out of pride, preferred to look the other way. His name was Robert Conquest, and he published a book where he explicitly stated that Stalin had killed millions. No one recorded it, no one mentioned it. It's curious how cultural elites, who proclaim themselves lovers of truth, turn into inquisitors when someone shows a truth that is inconvenient to them. Decades later, the Soviet Union fell, the archives opened, and… surprise! Everything Conquest had said was true. So his story is not just about a man who was right. The real question is: who are the Robert Conquests of today? Which voices are documenting uncomfortable truths while academics smile, journalists ridicule them, and elites call them conspiracy theorists? Because if history teaches us anything, it is this: the truth does not disappear; it is simply ignored until it becomes impossible to keep pretending. And when that moment arrives—the moment when everything is revealed, when the facts leave no room for ideological faith—those same people who once denied reality rush to say they always knew it. Conquest knew them well. Millions of people disappeared between one census and another. If there were dead, they were “unavoidable historical costs.” But Conquest did not join the applause. One can almost imagine the spectacle: the old intellectuals adjusting their glasses and saying, “of course, Conquest was right,” as if they had not ground him to dust twenty years earlier. In the sixties, while he was gathering testimonies from refugees, analyzing censuses, and comparing impossible figures, Western universities were living their romance with Moscow. But the topic that should keep us awake is not that. They said there was no famine, that it was all Western propaganda. They were lying openly. And the numbers don't lie. The state confiscated the grain, prohibited travel, and denied international aid. The same academics who despised him began to cite him with a respectful air, as if they had always supported him. And for these lies… he won a Pulitzer Prize. That's how prestige works: it rewards those who lie elegantly and expels those who tell the truth with data. Decades later, when the Soviet archives confirmed every one of Conquest's calculations, his publisher asked if he wanted to change the title for the new edition. Or worse: he had underestimated it. He had that annoying habit of double-checking the numbers. That's how atrocious it was. Meanwhile, the New York Times correspondent in Moscow, Walter Duranty, wrote the opposite. But it was too late. Millions of human beings… erased from the map by the man the world was still trying to sell as a great modernizer. The response from Western intellectuals was exemplary, as always: they called him a propagandist, a reactionary, a CIA agent, a Cold War lunatic. Traveling to Moscow was the new intellectual tourism. They returned dazzled, saying that the future was being built there, among the gray factories and eternal speeches. Because for twenty years, telling the truth was their worst crime. Now, this story is not just about communism, or even Stalin. It's about something deeper, more uncomfortable: how intelligence, when mixed with ideology, becomes a moral anesthetic. It's about how intellectuals, convinced of their moral superiority, can justify atrocities as long as they are committed by the right side. Millions of people, not metaphors or exaggerations. To say out loud what others preferred not to see. His book “The Great Terror” documented Stalin's purges with surgical precision. While villages were dying of hunger, the warehouses were full and the grain was being exported. And what was his crime? And how the fear of looking ridiculous—of admitting one was wrong—can lead brilliant people to defend the indefensible. The archives closed the debate. Time to do the math. In 1968, a British historian—one of those who prefer archives to applause—committed an insolence. Years later, he published “The Harvest of Sorrow,” a brutal investigation into the famine in Ukraine: the Holodomor. And he, with that dry British humor, like a leaf in autumn, replied: “Yes, put ‘I told you so, idiots.’” It was a joke, of course, but also a confession. That catastrophe was not an accident; it was a political decision. Conquest was right. At Harvard, Cambridge, Paris… they spoke of “Soviet industrialization” as if speaking of a humanist miracle. That's it. Simply, they did not exist.